Jewel’s Apologia and the Sturges Family

Jewel’s Apologia and Books Reunited — The Sturges Family

It is always a pleasure to receive one of the periodic catalogues from Blackwell Rare Books. Beyond the basic bibliographic

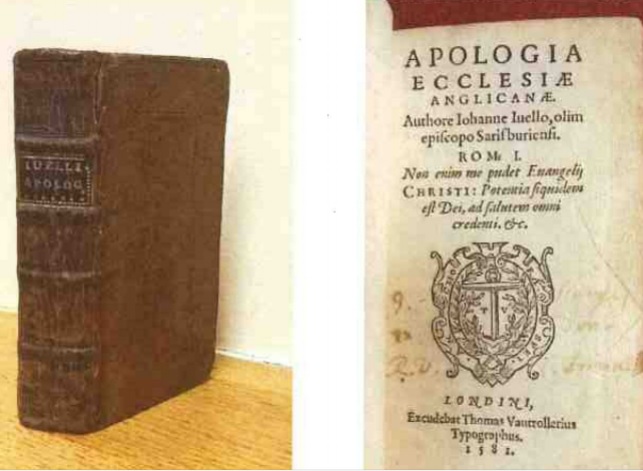

information on the books that are for sale, they often contain a wealth of supporting information about the titles and come with many useful illustrations. Although the prices are generally beyond a modest retirement income there are occasionally items that pique my curiosity. Such was the case with the recent catalogue B196 which included a 1581 copy of John Jewel’s Apologia Ecclesiae Anglicanae, published by Thomas Vautrollier. The Apologia was originally published in 1562 and represents the first systematic attempt to justify the organisation and intellectual position of the Anglican church against Roman Catholicism. Bishop Jewel was an important theologian and his views influenced Anglican beliefs over many generations. The work was translated into English in 1564 by Lady Anne Bacon, who was a daughter of King Edward VI's tutor, and in 1614 a Greek version was translated by John Smith and printed in Oxford by Joseph Barnes. This greek translation is bound with the Vautrollier copy.

The book went through man yeditions over the years and Bishop Bancroft later ordered that a copy should be displayed in all churches. Thomas Vautrollîer, the publisher of the 1581 edition, was a Huguenot refugee who worked in both London and Edinburgh and gained a high reputation for the quality of his printing work. One of his apprentices, Richard Field, later went on to become Shakespeare's first printer.

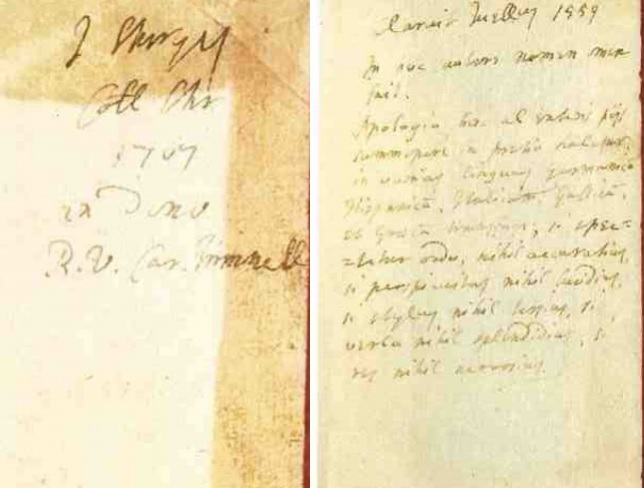

Although the volume is interesting in itself the provenance provides an unlikely link with another early printed book which is held in Aberystwyth University. The Blackwell catalogue suggested that an early owner might be one John Sturqy of Christ’s College in 1707, but a more likely identification seems to be John Sturges. He matriculated in 1702, was a scholar in 1702/3, was awarded a BA in 1705/6 and became an MA in 1709. He later went on to ordination, eventually becoming Rector of Wonston in Hampshire in 1723 and a Prebendary in Winchester cathedral. He died in 1740 and has a memorial grave slab in the cathedral. We know relatively little of the career of Sturges as a prebendary canon, but a near contemporary, Edmund Pyle, suggested that "the life of a prebendary is a pretty easy way of dawdling away one's time; praying, walking, visiting; and as little study as your heart would wish", so perhaps he led a fairly quiet life.

Sturges received the book as a gift from one R.V. of Emmanuel College, although a search of Venn has so far failed to identify who

this might be. He inscribed his name again on the fly leaf and also made some notes in dog latin about the various foreign language summaries of Jewel, indicating some dissatisfaction with style and content.

Sturges seems to have been in the habit of writing notes in his books during his time at Cambridge. In Aberystwyth University Library there is a volume of Pindar, published in 1620, which was given to him by his father, another John Sturges, in 1706. The father, like grandfather Thomas Sturges (BA1611/2), also attended Christ's College, becoming a BA in 1670/1 and obtaining his MA in 1674. He too had a variety of clerical appointments, ending up as Rector of Glatton, and Archdeacon of Huntingdon, before his death at the end of 1725. He is buried in the chancel of Glatton church. The Pindar volume also had some acquaintance with Emmanuel College, since there is a note of George Walker as an owner. Venn lists two possible Walker candidates, though the more likely one seems to have gained his BA in 1691/2 and then been a curate at Offord Cluny, also in Huntingdonshire, which may account for the Sturges link.

John Sturges junior provides some brief summary of Pindar’s life and work in his notes, and also includes some greek text, so both volumes demonstrate some familiarity with the language. However, this would have been fairly commonplace for an educated member of clergy at this time. It is tempting to look forward some century and a half to the writings of Anthony Trollope. His Last Chronicle of Barset, published in 1867, has Josiah Crawley, Perpetual Curate of Hogglestock, with his collection of “dog’s eared books from nearly all of which the covers had disappeared. There were the two odd volumes of Euripides, a Greek Testament, an Odyssey, a duodecimo Pindar, and a miniature Anacreon”. Crawley takes great pride from his greek scholarship and ensures that his children are trained to it, even amidst his troubles over the stolen cheque. “Now for Pindar, Jane” he ' said, seating himself at his old desk”.

Doubtless such scholarly traditions were maintained ìn the Sturges household. John Sturges junior married Margaret Lowth, the daughter of another Winchester Prebendary, William Lowth, the biblical scholar, who produced an important Commentary on the Prophets. They had a single son, yet another John Sturges, who attended New College, Oxford in the 1750's and went on to become both Prebendary and Chancellor in Winchester. He was involved in a minor religious controversy with RC Bishop John Milner at the end of the century, taking offence at some statements about Bishop Hoadly in Milner's History of Winchester, and producing Reflections on the Principles and Institutions of Popery, in response stimulating the production of one of Milner's most important works, Letters to a Prebendary, in 1800. Sturges died in 1807 and is also commemorated by a memorial slab in the cathedral.

In the next generation his son William Sturges-Bourne went into politics rather than the church, since he became a friend of Canning, holding various government appointments, including briefly the position of Home Secretary in 1827. He is the subject of a couple of satirical prints entitled Cottage Amusements, by the bookseller and engraver Samuel William Fores. William is remembered for his work in support of the 1819 Poor Law reforms. The family were based at Testwood House near Southampton until the 1890’s when it was sold out after the death of an unmarried daughter, Anne Sturges-Bourne, and presumably the contents of the house were auctioned off at the same time. The family were fairly comfortably off in the first half of the 19‘ century, following the receipt of a large inheritance in 1822, and Anne Sturges-Bourne was later painted as Autumn by Sir Charles Eastlake. Anne wrote some children’s tales and was influential on the writings of the novelist Charlotte Mary Yonge. Recent studies in Southampton University have demonstrated that “the stories written by Anne... were recognised in contemporary Tractarian circles as important contributions to the establishment of Anglo-Catholic doctrine for future generations”. It is not clear where John Sturges’ early books may have travelled over the past three centuries, although it is quite possible that they will have stayed in the family. However, this chance find relating to a former fellow member of Christ’s College, whose books are now briefly reunited in Aberystwyth, serves to demonstrate how one clerical family has influenced and itself been influenced by religious thought across the centuries.

Bill Hines (whh@aber.ac.uk)

December 2019