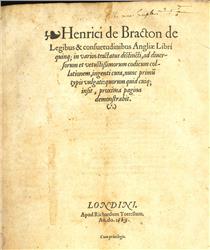

The Aberystwyth Bracton 450 years on.

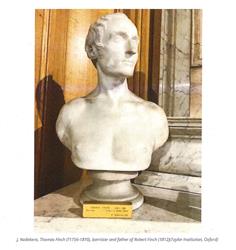

A new display to mark the 450th birthday of one of our main legal texts – Bracton – On the Laws and Customs of England, first published by Tottel back in 1569. Copies currently on sale in the second hand market start at around £7500 and so we are lucky to hold a copy on long term loan from the nearby Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies. You can read more about Henry de Bracton and the importance of his work at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_de_Bracton . I have spent some time looking at the provenance of this copy and unearthed quite an interesting history – from its first printing in 1569 by Tottel, with the distinctive Hand and Star watermark employed by the publisher, who is now buried at Wiston in Pembrokeshire. Through the 16th and 17th centuries the book was owned and annotated by several lawyers, including some from Inner Temple. In the 18th century the book passed to the legal writer Thomas Finch, commemorated with a bust by the famous sculptor Nollekens, and then to his son the Rev. Robert Finch, who was an associate of Shelley and Keats and spent much time in Italy. He provided one of the first accounts of the death of Keats and this is on display alongside the copy of Bracton. After Finch’s death in 1830 his collection passed to his secretary Enrico Mayer, one of the early supporters of the Risorgimento and a prominent Italian educationalist, who was imprisoned for his beliefs, and then the book passed to the Taylorian Institute in Oxford. They disposed of it as a duplicate in the 1920’s and it became part of the collection of the Welsh historian Sir John Goronwy Edwards.

The Aberystwyth Bracton 450 years on: A Study in Provenance

Henry de Bracton was a cleric and jurist in the 13th century and his De Legibus et Consuetudininbus Angliae represents the first major attempt to collect and interpret the principles of English law. Richard Tottel was an early printer in London, and was awarded a patent to publish books on the common law from 1553. In 1569 he produced the first printed copy of the Bracton text, reputedly from twelve surviving manuscripts. Tottel’s publishing work was carried on at the sign of the Hand and Star near Temple gateway and interestingly the paper in the volume carries this distinctive watermark. Tottel amassed significant land holdings in the London area over the years but retired to Pembrokeshire towards the end of his life and died in Wiston in 1593. The publication and significance of the Tottel Bracton has been well documented in a 2011 paper by Ian Williams, although he does not seem to have known of the Aberystwyth copy. He notes that work on the lengthy Bracton text consumed most of Tottel’s energy during 1569, to the extent that he needed to farm other work out elsewhere. We do not know how many copies were printed, a typical print run for the period of 1000 copies seems large for what was a specialist text. Williams identified some 30 surviving copies for his research, although other copies exist in British libraries and indeed six are currently listed for sale in a major second hand online resource, commanding hefty prices.

The Aberystwyth copy has enjoyed quite a varied career over the past five centuries. There is an early partially erased signature on the title page, probably of late 17th century or early 18th century date, indicating that the volume was in Inner Temple at that time. The first page of the commendation has a signature for an E. Jenings, who may possibly be Edward Jenings, admitted to Inner Temple in 1729. From then onwards we have a rather clearer view of the book’s travels. There is a bookplate for Thomas Finch who was a student at St. John’s College Oxford in the 1770’s and called to the bar from Inner Temple in 1781, later becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society. Thomas was responsible for the revised edition of Precedents in Chancery, 1689-1722, also known as Finch’s Precedents, published in 1786. He died in 1810, and is commemorated in a bust by Joseph Nollekens now held in Oxford. From Thomas the book passed to his son Robert. He was a student at Balliol College Oxford from 1802 to 1805 and, although he was ordained in 1807, became something of an antiquarian, spending much of his life in Italy. He was an associate of both Shelley and Byron’s circles and other expatriate artists, although often regarded by them as a ridiculous figure, styling himself as a retired lieutenant colonel to make travel easier, Mary Shelley describing him as Colonel “Calicot” Finch !

Finch acted as a mentor and benefactor to a young student from Livorno, Enrico Mayer, the son of family friends, naming him as life beneficiary in his will since he died childless of malarial fever in 1830. Robert is commemorated by a memorial, erected by his wife in the Protestant cemetery in Rome, far larger and more ornate than those for either Shelley or Keats. Finch had written to Meyer in 1825, “I heartily wish the being with me in my library was not fancy. There is abundance of room for a second large library table, at which to see you seated and employed would be almost too joyful a spectacle for me”. Again in 1827, “I fancy what pleasure you would have in arranging my noble library, which I mean to transport here [i.e. Rome]”. Mayer took up a post as secretary to Finch at the end of 1828 and did indeed spend time arranging the library, which had been moved to Finch’s residence in the Palazzo del Re di Prussia on Monte Cavallo around that time. Mayer also became a noted educational scholar and was closely associated with the Risorgimento, to the extent that he was imprisoned for his political views in 1840. By this time he had arranged for Finch’s extensive collection of ten thousand books and artworks to be transported to Oxford University, intended by Finch as their ultimate home. For many years the books were housed in a room in the newly founded Taylor Institution in Oxford. A catalogue of the collection, compiled by George Parker, was published by Hall and Stacy in 1874 and Mayer died in 1877. The collection was later reorganised and divided between the Bodleian and Taylor Institution with duplicates being identified and disposed in the early 1920’s. The volume then passed into the hands of the eminent Welsh medieval historian Sir John Goronwy Edwards, who died in 1976, and thence it came to the University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies, and is currently on long term loan to Aberystwyth University.

The volume is extensively annotated throughout. Many of these are simple underlinings for emphasis, but there are also many cross references to other folios within the work dealing with particular issues and it is clear that at least one of the many readers over the centuries had an extensive and thorough working knowledge of the text. Some of these marginal annotations are very complex, e.g fol 241b. There is evidence of an early Elizabethan hand on a few pages, e.g folio 18a and again on 41a. A couple of later annotations in an 18th century hand at folio 61b and 65a make reference that “the law is now otherwise” – as might be expected with such a historic work. Again at folio 118b there is reference to the “law of high treason is altered in this particular…”. It has been suggested that many lawyers used such texts in the compilation of their own commonplace books. By the time that the book came into the ownership of the Finch family it would have been supplanted by Blackstone and seen as a historical artefact rather than a working text. Indeed Mayer makes reference to searches of Blackstone to understand the contemporary law relating to his new inheritance, which he may have regarded as a burden.

Bill Hines (whh@aber.ac.uk)

Sources

J.H. Baker - chapters in Cambridge History of the book in Britain vols 3+4 , 1999/2002 (chaps on Books of common law v3, English law books v4)

David Thomas - The Faithful Shepherd and me: a personal odyssey. Bodleian blog 2018/9

ERP Vincent - 'Robert Finch and Enrico Mayer' . 29 Modern Language Review 1934

Ian Williams - 'A medieval book and early modern law'. 79 Legal History Review 2011

DEC Yale – 'Of no mean authority', in On the Laws and customs of England 1981 pp383-396]

See also Byrom paper on 'Richard Tottell – his life and work'. Library 1927 pp199-232 and Elizabeth Nitchie, The Reverend Colonel Finch. New York, Columbia 1940. Also DNB etc .