Ron Underdown

Memories of Halling in the 1940’s by Ron Underdown

I was born in Halling and five years old at the outbreak of the second world war in September 1939. The following is a collection of my childhood memories of life in Halling in the 1940’s.

Welcome to Halling in 1940.

Imagine a view from the church along the High Street towards the railway bridge without a vehicle in sight. A line of mature elm and sycamore trees in some of the larger front gardens and ornamental iron railings on the retaining walls. It wasn’t long, however, before the war began to take effect on surroundings. The railings, together with others in the village, and a small field gun from the First World War (1914-1918) positioned by the church lych gate as a memorial to Sgt Harris VC, were removed for scrap early in the war. Small squares of metal are still apparent in some of the coping stones on the walls. Gas was used for street lighting, except during the ‘black-out’ in the war of course. A pilot light in each lamp was left on and a man using a long pole with a hook, to reach inside the lamp, activated a rocker-arm to turn the gas on or off. Halling, with a variety of shops, was quite self-sufficient but bread came from Gammon’s bakery in Snodland – first by horse-drawn, then a motorised van. Orders could be placed with Harris the grocer and Ashby the butcher for delivery by errand boys riding bicycles with large baskets in front. Milk was delivered by handcarts from local dairies with churns of milk which was served by half-pint scoops poured into a customer’s jug, a practice replaced by milkmen delivering bottles of milk. School children were issued with a small bottle each day. Although milk was delivered almost daily, keeping it usable and to prevent waste, particularly in hot weather, was a problem. Bottles would be stood in cold water or, as a last resort, the milk would be boiled. Not particularly appetising in tea!

Allotments, necessary to provide food for the table and help with families’ budgets, became important during the war when people were asked to ‘Dig for Victory’ to help ease food shortages. The main allotments were located between the cemetery and chalk pit (the sandstone parapet of the nearby railway bridge shows areas of wear where gardeners sharpened their knives); another was adjacent to the railway line, where the road leading to Howlsmere Close and the school is now; the houses in Britannia Close occupy another; there were others between houses in the High Street and the ‘Institute’s’ sports field; another opposite the Vicarage and one adjacent to Stake Lane, part of which is still in use.

The village by-pass did not exist and neither did the lake as we see it today. The area was created by the excavation of a chalk hill and the depth by dredging. The source of water, from springs, is part of the local water authorities’ supply. The hill was significantly higher than the remaining cliff face would suggest. The slope towards Kent Road made a great toboggan run! Halling Working Men’s Club (the ‘Institute’), was an impressive and imposing building in the centre of the village. It had bars for members, a family room and meeting rooms downstairs while upstairs there was a snooker room and a large hall with a stage, back-stage facilities and drapes (curtains) used for dances and wedding receptions. The plus side for children was a superb central bannister on the stairs to slide down. During the war, shows were put on by the Follies’ Concert Party here in the Institute and in other local villages often supporting fund-raising activities. The photograph was taken during a show in aid of the prisoners of war benevolent fund which appeared, with an article, in the South Eastern Gazette on 2nd December 1941.

The Institute’s sports field (the ‘Rec’), had a pavilion built of wood with separate changing rooms for teams, a storage room for kit and a viewing veranda. Viewed from the pavilion, there were tennis courts in the bottom left hand corner of the ground. Already deteriorating (chain-link fencing rusting and broken), with lack of maintenance during the war, the courts were never used again. Children were allowed to use the goal-posts for a kick-about and could play cricket off the playing area. Travelling fairs with chair-a-planes, roundabout, swings etc. would sometimes use the non-playing area of the ground.

Home entertainment included playing cards and board games, reading or listening to the wireless/radio which required a large battery pack and an accumulator (like a small, glass car battery) which had to be recharged, to provide power and an external aerial to pick up the signal. A wire from the radio to a copper strip set in the ground outside, provided an earth. Externally, going to the pictures or cinema was popular. Programmes normally included the main film, a ‘B’ film, Pathé news, advertisements, trailers of forthcoming films and, sometimes, a film ‘short’ or cartoon. There were cinemas in Snodland, Malling, Strood, Rochester and Chatham served by regular bus services (last bus from Chatham around 10:15pm) and to those in Maidstone by train. The Wardona in Snodland was a favourite since one could walk if necessary and with ‘rolling’ programmes one could see the main film twice. One could go roller-skating at the Casino in Rochester and see a live variety show at the Empire in Chatham. Halling had its own resident ‘Bobby’ or policeman, complete with bicycle and once, albeit briefly, its own purpose-built police house (1950’s). The Marshes were prone to regular flooding when the sea (river) wall was breached or overflowed. Soil/Clay was excavated and used to raise the height and build a more substantial wall from what is now the step-stile at Low Meadow around to the Elm Haven boat yard at North Halling. Italian prisoners of war provided the labour. The dykes, formed when the soil was excavated, helped to drain the marsh although these are now quite silted-up.

The Ferry, even when the bridge was built, provided an important link with Wouldham, particularly for some residents who needed to get to work on this side of the river. Some caught a bus or train while others brought their bicycle with them. It says much for the skill and strength of the oarsmen, who sometimes rowed standing up to combat the strength of the tide, to get the boat with its occupants to a small landing area the other side of the river. 3 It is perhaps difficult today to imagine that Halling once had a Station Master, whose house overlooked the station; the ticket office and signal box were manned and in winter an open fire warmed the waiting room. Stations also held a best-kept competition. Steam engines were still a major force, even on some passenger services and coal and parcel wagons would be shunted into the sidings adjacent to Station Road.

Each row of houses in Halling had names e.g. Manor Terrace, Hilton Terrace. Large detached houses also had names such as ‘The Paddock’ and the three-storey property in the High Street, empty throughout the war, was ‘Bedford House’. Most houses were rented and a Rent man called each week to collect the rent. The majority were without electricity and relied on gas lighting (with very fragile gas mantles) or candles for light. Candle holders with handles were used to provide light to go upstairs and night-lights, a very short candle with paper surround, placed in a saucer of water were used, particularly in children’s rooms. Kitcheners (a fire with a built-in oven) usually found in a living room, was used for roasting and baking. The fire was fed from the top by removing a round plate with a special tool. A couple of gas rings in the scullery were used for boiling kettles or cooking in saucepans. Pennies were fed into a gas meter to maintain supply and periodically the Gas man would call to empty the meter. The coins were counted and usually a few were handed back. Eventually the kitchener was replaced by an open fire with a tiled surround and the two gas rings by a gas cooker. The main fuel used on fires was coal, which was delivered. Bags of coke (partially burnt coal) could also be purchased from the gas works in Snodland (close to railway station). My brother and I used a cart, made from wood and a set of pram wheels or, with snow on the ground, a sledge to carry the bags home. Logs of wood were sometimes used. With all open fires a long handled toasting fork was used to toast bread or crumpets.

Wash day for mothers was a long, arduous affair. Using a Copper (a bricked-in, round metal tub with a fire underneath), the tub had to be filled with water and the fire lit to boil the washing. A wooden lid was placed on top. After boiling, as appropriate, items were removed using a copper stick (short, wooden pole) to be hand washed in the sink using a hard, green soap and at times a scrubbing board. The washed items then had to be rinsed in cold water and rung-out, again by hand. A hand operated mangle squeezed out excess water and as the items left the rollers they fell into a basket. Children sometimes helped by turning the mangle wheel. After ‘shaking-out’ the washing was pegged to a line in the garden to dry. Ironing the dried washing was not easy either. A blanket was placed over the dining table (not varnished). Cast-iron irons were heated, either on top of the kitchener or gas ring and a cloth used to protect the hand. The temperature of the iron was tested by wetting the tip of a finger and lightly touching the surface of the iron. Two irons were used, one being heated while the other was in use. Once ironed the items were aired on lines close to the ceiling and/or on ‘clothes horses’. Generally, there were no bathrooms. The toilets were outside and for one’s ablutions there was a bowl in the scullery sink or, for a bath, the option of either heating saucepans of water to fill a tin bath or to visit the public baths in Snodland. Water could be heated to fill the copper and bathe small children.

With no double-glazing or central heating, in winter ice could be found on the inside of bedroom windows. Hot water bottles, some of stone, were much in demand. Paraffin heaters, an obvious fire risk if knocked over, were also used. A paraffin lantern hung by the side of the cistern in the outside toilet, helped to prevent this freezing solid. Some households may have had one, even two, bicycles but generally people either walked or used public transport to get about.

Children walked to and from school including at lunch time, carrying their gas masks in the early part of the war. With traffic largely industry or trade related and very few privately owned cars it was not uncommon, particularly of an evening, for children to play in the street until a vehicle came along. 4 The local doctor, resident in the village, had morning and evening surgeries, visited patients at home on his rounds and could be called to attend at any time. Church fetes were held in the Vicarage garden and the adjacent field. Children from the school were allowed to use the field during the summer. The Vicarage hall was used as a youth club for a few years, later for light industrial use. School summer holidays were taken late in the year, running into September, allowing families, mainly women and children, to go hop-picking to earn extra cash. Farmers arranged transport, a coach if you were lucky or a canvas-topped lorry with benches, for an early morning pick-up – long before the sun cleared the heavy, morning mist. Those of us who went to Pye’s farm in Dean Valley at Cuxton, went by Beaney’s bus. One of the first tasks was to get a fire started for the first brew of tea of the day. Children collected dead branches from the nearby wood for the fire. The bins used for picked hops were of loose sacking attached to a wooden frame, a dividing panel formed a half-bin allowing two different groups of pickers. The hop vines were cut down by men using knives on long poles and handed to the pickers. Adults sat on the bin frame as they picked while children picked into boxes or upturned umbrellas. When enough hops had been picked a ‘binman’ came round with a bushel basket to measure how many each picker had produced. The ‘binman’ would check for any leaves among the hops and would sometimes refuse to measure until the leaves were removed. The hops were emptied into a large sack and a tally kept of the number of bushels picked for payment (a few old pence per bushel) at the end of the week. When the hops were small an increase in the amount paid per bushel was made, often following complaints from the pickers. Special memories of hop-picking for me include collecting wood for fires with my brother, the smell of hops, my mother sitting on the bin frame picking, picking hops (regrettably not as many as I should have done) into an upturned umbrella with my brother and sister and blackened fingers from picking, the occasional visit of the farmer riding a magnificent looking chestnut coloured horse, a long walk home when picking was rained-off for the day, the general good humour of the pickers and especially the taste of tea brewed in a billy-can over a wood fire – helped, perhaps, by the condensed milk used.

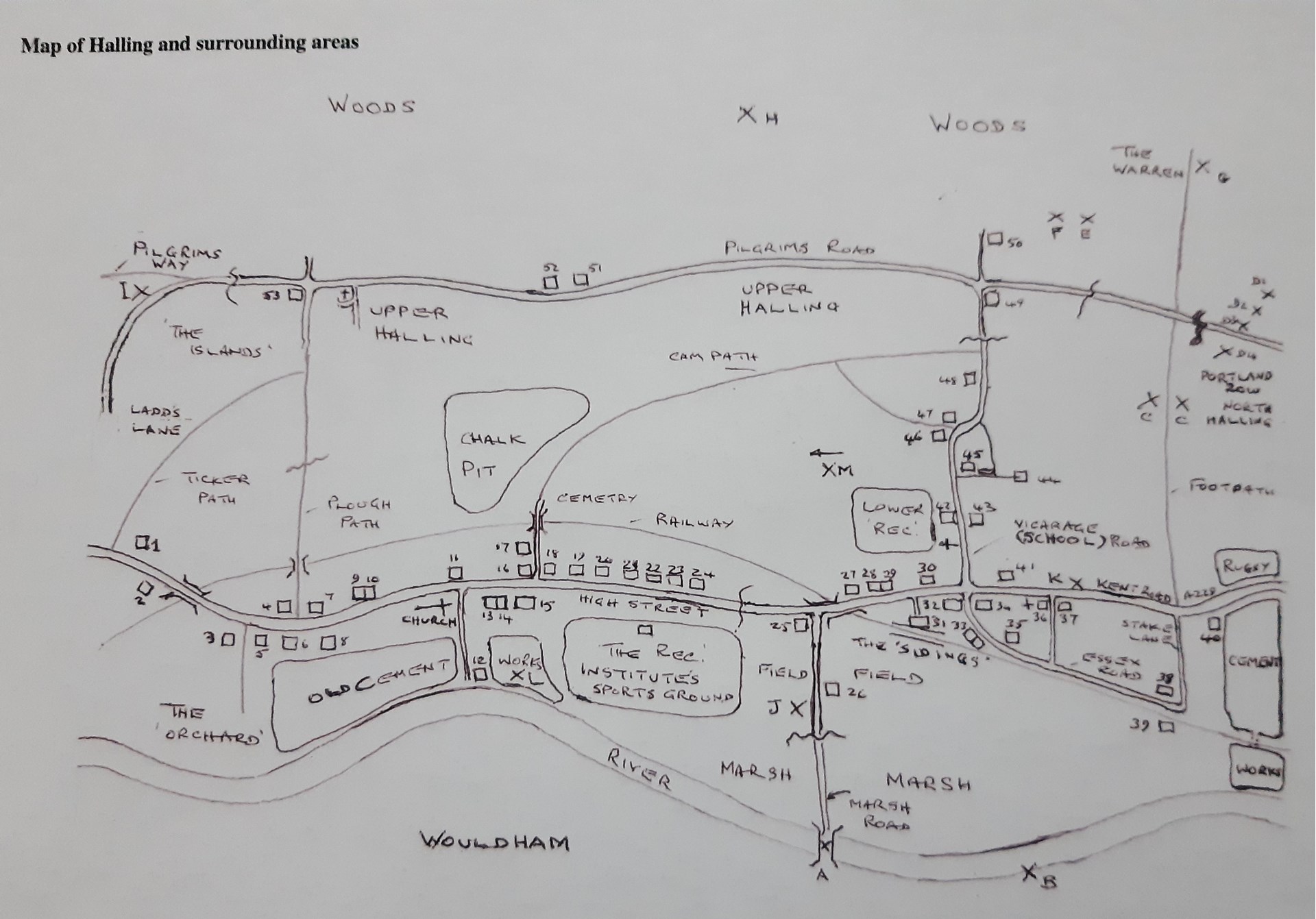

Wartime Events and Incidents Army personnel built a bridge across the river and the Marsh Road (reference “A” on the map below). At the time the bridge provided the only alternative river crossing to the ancient stone bridge at Aylesford, between Rochester and Maidstone. Only pedestrians and military vehicles were allowed to use the bridge which was removed soon after the war. As witnessed when living in Manor Terrace in the High Street, whilst standing in the back yard of our house and looking towards the Marsh Road, I saw a Hurricane fighter, in flames, pass low over the houses in a shallow dive heading towards the river. It was a sunny day and one could clearly see the pilot parachuting to the ground. Having climbed on to the top of the air-raid shelter (which was below ground level) I could see perhaps twenty or more people running across the allotments and the ‘Rec’ towards the crash site (reference “B” on the map below). A published account states that: “On Sunday 13 October 1940, Pilot officer Jack Ross DFC, a member of 17 Squadron based in Debden, Essex, was scrambled to intercept enemy aircraft heading for London, over Dartford. Pursuing an enemy plane, in and out of cloud, his aircraft (Hurricane P3536) was hit by anti-aircraft fire. Although wounded he removed his flying helmet, bailed out and parachuted safely to the ground. The aircraft crashed at 13.54 into the east bank of the Medway at Wouldham near Rochester. The pilot, with injuries to both legs, was taken to Gravesend hospital”. Further details available at http://www.wouldhamvillage.com/hurricanewreck.html.

There were three other air crashes although details are not verified. A Mosquito fighter bomber crashed and burst into flames in the woods above the ‘Warren’, adjacent to the path leading to Dean Valley. The smoke plume could be seen from the village (reference “G” on the map below). An American Mustang fighter crashed in a field adjacent to the Pilgrim’s Way and the sharp bend in Ladd’s Lane at Upper Halling (reference “I” on the map below). A British bomber believed to be a Wellington, crash landed at night in a remote spot on the opposing slope to that at Upper Halling. One could see the path taken by the aircraft, due to slight damage to trees and bushes on the slope, until it came to rest at the edge of the wood. There was some speculation that the site could have been a ‘dummy’ airfield set up to encourage enemy bombers to drop their bombs where they could do least damage. After the sites were cleared, boys searched the area for ‘finds’ such as fragments of metal or Perspex (from which rings could be made). Just as, following air raids which were usually at night, they would look for pieces of shrapnel from anti-aircraft shells or other related items.

Bombs fell on North Halling, approximately half a mile north-east of Rugby cement works. An aircraft dropped four bombs. One fell in the hills adjacent to the chalk pit, the second in my grandfather’s back garden, the third demolished the end house in Portland Row (fortunately no fatalities or serious injuries) and the fourth fell in a field. (reference “D” on the map below). Two Doodlebugs or flying bombs fell, close together but at different times, on a hill adjacent to Lingham’s farm at Upper Halling. The second, during the day, which my brother and I happened to witness. I was walking across a field next to Marsh Road when the doodlebug appeared to my right from the direction of Wouldham, quite low and its rocket engine firing unevenly. My brother, waiting for me to join him and friends at the ‘Sidings’, saw the doodlebug approaching head-on and recalls that as the engine cut-out briefly the nose of the doodlebug dropped down a few feet before levelling out again when it re-fired. It was rapidly losing height. Moments after passing there was a huge explosion and briefly a large ‘fireball’. It seemed to be much closer than it turned out to be and fortunately fell where it did little damage. Both are shown as dots on the map printed in the Kent Messenger on June 15 1973 headed ‘When the Doodlebugs fell on Kent’ (references “E” & “F” on the map below).

In fields either side of the footpath leading from Kent Road to Pilgrim’s Road, rows of poles were erected and joined together by thick wire at the top. Perhaps to deter glider landings (speculation) - (reference “C” on the map below). A large, open sided building close to the ferry, stored large quantities of small barrelshaped objects and was patrolled by a watchman (reference “L” on the map below). The chalk pit was used by the military using live ammunition. It is sad to recall that some young lads accessed the area and removed an item which later exploded, causing life-changing injuries to at least two of them. There are reports that PLUTO (Pipe-Line Under The Ocean) which carried fuel across the country and the Channel to supply military vehicles following the D-Day landings in France, passed through Halling. During the war I recall my brother and I ‘inspecting’ a trench in what was then a field (now Vicarage Close) and being chased by the farmer! Given the fact that he bothered to chase us out of the field, it does perhaps suggest that the trench was of some importance. Could it be the route of PLUTO? (reference “M” on the map below).

The following describes locations and points of interest that have been highlighted on the map below:

The Orchard with not a fruit tree in sight was an area of grass by the river and on the edge of the old cement works, bounded on one side by a small silted-up river inlet, which contained the remains of a rowing boat. The area was big enough to play rounders and popular for picnics. The Islands referred more to the route taken by road rather than an area of land – ‘a walk around the islands’.

The Warren, an attractive spot. A grassed hill-top with excellent views of the valley, backed by beech trees and the woods beyond. Noted, in season, for the carpet of bluebells among the trees. Reached by footpath from Pilgrim’s Road, with a slight incline and then a steep climb up a hill – another good toboggan run. Much has changed since with the erection of boundary fences and a monstrous pylon on the ridge creating a permanent ‘blot’ on the landscape. The woods retain their appeal however and the views are well worth the climb.

The Chalk Pit. One of a number but mentioned for several reasons. Towards the end of the war it was used as a training area for soldiers using live ammunition. Before and after that time it was used as a play area by children. Noted for primroses and wild strawberries in season. Based entirely on childhood memories (it was quite picturesque and flat) it would make a great recreation area for walks etc.

Old Cement Works. Chimneys and main factory buildings demolished and then left.

The Sidings. An area adjacent to the railway station where, formerly, loaded cement trucks were brought from a then active cement works to join the railway system. Now overgrown, it was a favourite play area for boys with trees to climb, particularly the beech tree next to the platform, etc.

Lower Rec. Recreation ground and Halling Minor’s (under 18’s) ‘home’ football pitch.

The following is an index to numbered locations on the map below: 1. Fissenden’s farm. 2. Twelve Houses – a row of cottages whose front steps stopped on edge of road. 3. The ‘Walnut Tree’ – a thatched-roofed off-license 4. ‘The Plough’ pub 5. Feathersone’s shop – occupier of house in Hilton Terrace sold potatoes, sweets etc. 6. Bowling green. 7. Hayward’s builders yard. 8. Bradley’s – shop in front selling sweets and Lyon’s ice cream, at the back a transport cafe. 9. Harris’s (later combining with shop next door, the CO-OP) – grocers. 10. Barbers. 11. The ‘Five Bells’ pub. 12. The ferry. 13. Shop – empty during war but a number of uses after. 14. The Post Office – also sold ladies’ dresses, knitting wool etc. 15. Halling Working Men’s Club – the ‘Institute’. 16. Ashby’s – butcher 17. Yard where the butcher kept pigs. Later became Bert Cook’s coal yard who delivered coal by horse and cart. 18. The ‘Rose and Crown’ pub. 19. Mid-terrace house converted into Gore’s fish and chip shop. 20. Root’s/Bourne’s shop – sold sweets and bottles of pop called Penny (later Penny-Ha’penny) Monsters and sometimes home-made ice cream. 21. Bill Road’s – shoe repairer and shoe sales. 22. Holme’s shop – sold sweets and Wall’s ice cream. 23. The ‘Homeward Bound’ pub. 24. Rook’s – lending library. 25. Allen’s – dentist. 26. Sewage treatment plant. 27. Haye’s – school dentist. 28. Chapman’s – butcher. 29. Hooker’s – greengrocer 30. Horner’s – newsagents. 31. Railway station. 32. Botten’s garage. 33. Squire’s – butcher; adjacent shop empty. 34. Beadle’s – ironmongers also sold paraffin, candles, kindling wood etc. 35. Hearn’s – greengrocer. 36. Tidy’s – sold items of household furniture. 37. Mutimer’s (later Wraights) – grocers. 38. Feltham’s – dairy. 39. Faucheons farm. 40. End of Formby Terrace – Osenten’s farm. 41. The ‘New Town Social Club’ (‘The Bolshie’). 42. Fire station. 43. Doctor’s surgery. 44. Forrester’s farm. 45. The Vicarage. 46. School for infants (5-7 year olds). 47. School for older children (8-11 year olds). Head teacher’s house was in the grounds. 48. Water works – housed a huge ‘beam’ pumping engine. Wonder what happened to that! 49. The ‘Robin Hood’ pub. 50. Lingham’s farm. 51. Wraight’s – grocers. 52. Baker’s wood yard – made chestnut paling fencing. 53. The ‘Black Boy’ pub.

The following is an index to war time locations on the map: A. Army personnel built the bridge and the Marsh Road. B. Hurricane plane crash. C. Possible anti-glider landing arrangement. D. Four bombs dropped. E. Doodlebug crash site. F. Doodlebug crash site. G. Mosquito fighter-bomber crash site. H. British bomber crash-landing. I. American Mustang fighter crash site. J. Barrage Balloon site at bottom of field. K. Air-raid shelters built into bank. L. Special storage area. M. Possible route of PLUTO (speculation only).