Essential Caravaggio

This brief paper deals only with Caravaggio’s life from birth to his escape from the Papal authorities in Rome, following the killing of Ranuccio Tommasoni on the 29th May 1606, first finding refuge in the estates of the Prince of Colonna South of Rome and later escaping to Naples in 1606, where he could remain under the protection of this powerful family. Its aim is to clarify as far as is currently possible, details of his biography, concentrating especially on his life in Rome and to introduce the Hockney-Falco theory, first introduced in Secret Knowledge, published 2001. Hockney proposes that mirrors and lenses may have been utilised in Flanders as far back in the History of Art as the early 15th century. But Hockney and others also propose that Caravaggio within a very brief period, perhaps as little as a few years, took the use of optics a stage further, revolutionising the technique of painting by the addition of strong focused sunlight, or as Hockney put it, Hollywood Lighting and more refined convex lenses and or parabolic mirrors. Still disdained by many in the academic establishment, there are an increasing number of Caravaggio scholars and art commentators who support this concept.

Michelangelo Merisi Caravaggio was born on 29th September 1571, shortly after the Council of Trent had arrived at its agenda to counter the austere teachings of Luther and Calvin, including most importantly advice to artists as to how they should portray Biblical narratives, that is how it should be in a manner more relevant to it’s Catholic flock, avoiding references to narratives from the Golden Legend and the Apocrypha. Incidentally, it was also the same year that the Venetian alliance defeated the Ottoman Fleet at the Battle of Lepanto and almost exactly a year before the State sponsored St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of Protestants by Catholics in France in August 1572. Throughout Europe, Christianity, its dogma and how it should be practiced were inextricably linked with politics and power.

Thus Caravaggio was born into a world, in which throughout Europe, Catholicism was reasserting itself through the pronouncements of the Counter-Reformation. It was on the cusp of the 17th century, that Caravaggio would revolutionise and transform painting for ever, producing Naturalistic paintings, using models off the street to bring to life Biblical narratives in a way never before seen, images of theatre, drama, raw brutality and emotion that shocked, astonished and overawed the onlooker. Essentially, there is painting before Caravaggio and thereafter, with a profound difference in the appearance of paintings between the two periods.

Although traditionally thought to have been born in Caravaggio, a small town near Bergamo, more recent documentary evidence confirms that he was baptised in Milan. His father, Fermo Merisi, was a house-hold steward and architect to the Marchese of Caravaggio and his mother was Lucia Aratori. In the Summer of 1576, when Caravaggio was but five, Milan and the surrounding area were struck with Bubonic plague and within a year, he had lost almost every male member of the family. It is Andrew Graham-Dixon’s supposition that Caravaggio’s later troubled, unpredictable, volatile and dysfunctional personality was as a direct consequence of this experience.

He was first apprenticed to the Lombardy painter Simone Peterzano in 1584, under the protection of the Marchese Colonna and her family, the same year in which his mother died. He had sold most of his inheritance by 1590 and the rest by May 1592; the last documentary source confirming that he was still in Caravaggio, according to legal documents regarding the sale of land he acquired in his earlier inheritance, suggesting that this was done in preparation for a journey. There is also the suggestion from the accounts of his life in Milan by the biographers, Mancini and Bellori, that he was leaving, under a bit of a cloud, that he may have been involved in certain quarrels, wounding a girl, killing a fellow worker and the wounding of a police officer and that he may have been in prison.

About his journey to Rome, when he actually left Lombardy, where he went, one can only speculate, as so far there is no primary source material on his subsequent movements until the first documentary evidence of him being seen in Rome, around late 1595 to early 1596. Clovis Whitfield in The Trouble with Caravaggio 2014, now believes that everyone, including those who have written extensively on Caravaggio, such as Helen Langdon (Caravaggio, a Life), Andrew Graham Dixon (A Life Sacred and Profane) have been ‘led down the garden path’, by the 17th century biographer Guilio Mancini, whose estimate of Caravaggio’s age as twenty, when he stayed with a certain Monsignor Pandolfo Pucci (Mgr Insalata), in the Palazzo Colonna, when in fact, other evidence suggests that he was more likely two, or three years older. If this is the case, we have a gap of about three to four years in Caravaggio’s biography and the current dates on his early artistic output between 1593-7 would need to be revised.

Clovis Whitfield alludes to the earliest yet documentary proof of Caravaggio being in Rome as towards the end of 1595, just before a certain Pietro Paolo Pelligrini, a barber’s shop boy gave a sworn testimony first recalling seeing him, further substantiated by his confirmed occupation as a day-worker in the Sicilian, Lorenzo Carli’s shop by Cheisa San Luigi dei Francesi in early 1596. It should also be noted that since none of the paintings were dated, many of the early paintings, especially the ‘portrait heads’, were given dates on the basis of stylistic similarities and Caravaggio scholars have tended to space the paintings out to fill in the unaccounted for years. The sparseness of trustworthy primary source material also encouraged contemporary biographers, historians and writers, to speculate and fill gaps with inventive fiction. Fortunately, the dating for paintings from the St Matthew Trilogy in the Contarelli Chapel, commissioned in 1660 and onwards, is more trustworthy, where at least dated documentary proof for these does exist.

The little we know about his life in Rome and thereafter until his death in 1610, comes down to us from four principal biographers, three contemporary and one from after Caravaggio’s death. All were astonished to varying degrees by the novelty and naturalism that Caravaggio brought to his paintings. His original use of live models, with no life drawing as practised in Renaissance Classicism, friends, lovers, or mistresses and common folk off the streets, including prostitutes, most famously Anna Bianchini and Fillide Melandroni; and then there were the dramatic lighting effects he achieved and his ability to depict Biblical narratives, brought up to date in apparently mundane, everyday situations that had never been attempted before.

Traditionally, the most important testimony, has always been that of Giovanni Baglione (1566-1643), a painter very much at the centre of the art world in Rome and a member of the Accademia di San Luca, three times its president, a painter obsessed with his status, one who would have been intimately aware of Caravaggio, envious of Caravaggio’s success and most likely a reluctant biographer, whose objectivity should not be totally relied upon. Nevertheless, he is known to have referred to Caravaggio’s small head and shoulder paintings as, small head paintings portrayed in a mirror and statements such as the following on seeing The Lute Player, a young man playing the lute, who seemed altogether alive and real with a carafe of water and flowers, in which you could see perfectly the reflection of a window and other reflections of that room inside the water and on whose flowers was a lively dew depicted.

Then on another occasion, He would talk ill of all painters from the past, however famous they had been; for it seemed to him that he alone had made advances in his works beyond all the others of his profession.

These observations appear to strongly support the premise, that shortly after arriving in Rome, Caravaggio had discovered a technique, which allowed him to quickly produce copies of small paintings, to be sold, first in Lorenzo Carli’s bottega near the Saint Augustine Church and later in the establishment of Constantino Spada, a dealer in old paintings, in front of the Chiesa San Luigi dei Francesi.

The Flemish painter, art theoretician and biographer, Karel van Mander (1548-1606), was in Rome from 1573-77 and although not in Rome contemporaneously with Caravaggio, must have learnt of his exploits and fame from other returning Dutch and Flemish painters. In his Lives of Italian Artists, Part III of Het Schilder-Boeck, we find this very illuminating passage: Caravaggio’s belief is that all art is nothing but a bagatelle, or children’s work, whatever it is and whoever it is by, unless it is done after life and we can do no better than to follow Nature. Therefore, he will not make a single brushstroke without the close study of Nature, which he copies and paints.

And then a little further on, but one must also take the chaff with the grain: thus he does not study his art constantly, so that after two weeks of work, he will sally forth for two months together with his rapier at his side and his servant boy with him, going from one tennis court to another, always ready to argue or fight, so that he is impossible to get along with.

Floris van Dyck (1575-1651), another Flemish painter, who was in Rome around 1600 wrote, he has climbed from poverty through hard work and by taking on everything with foresight and courage, as some who will not be held back by faint-heartedness, or lack of courage, but who push themselves forward boldly and fearlessly and who everywhere seek their advantage boldly.

Giulio Mancini (1559-1630), connoisseur/art dealer/physician and biographer in his book, written in the first decades of 17th century Some considerations belonging to painting, which may please a gentleman, wrote This School, in this way of operating, is very observant of truth and keeps it always in front of him when he is working.

What is specific to the School is that they represent the light in combination with a source of light originating from above without reflexes, as is the light entered from a window in a room, whose walls are painted in black; in this way, everything bright becomes very bright and everything dark, very dark and this gives relief to the painting, but not in a natural way.

Giovani Pietro Bellori (1613-96), painter, antiquarian and biographer of artists, wrote later in the 17th Century in his, Lives of the Artists 1672, it is said that the ancient sculptor Demetrios was such a student of life that he preferred imitation to the beauty of things; we saw the same thing with Michelangelo Mersi, Caravaggio, who recognised no other master than the model, without selecting from the best forms of Nature and what is incredible, it seems that he imitated art without art.

The he began to paint from his own inclinations, not only ignoring, but even despising the superb statuary of antiquity and the famous paintings of Raphael, he considered Nature only to be the only fit subject for his brush.

When Caravaggio was shown the famous statues of Phidias and Glykon in order that he might use them as models, his only answer was to point out towards a crowd of people, saying that Nature had given him an abundance of masters

When considered together, what all these statements and observations in the 17th century have in common and most strongly suggest is that Caravaggio’s approach to painting, was a comprehensive change in perception, in fact nothing short of a revolution, which can only be explained by a eureka moment, a moment of inspiration. In other words, he discovered a way of representing reality by directly painting images on to canvas, without all the previously regarded essentials of a long period of Classical training, involving study of the Old Masters, the use of the imagination to dream up a composition based on a narrative, a thorough knowledge of iconography, meticulous planning and production of multiple drawings, or transfer cartoons etc. Its also evident from the testimony of various biographers, that Caravaggio disdained the current conventional rules of Classical Academic training and indeed, had but a low regard for the paintings of his most successful contemporaries, Frederico Zuccari, Giuseppe Ceasari and Giovanni Baglione.

Also worthy of mention are the police records, which whilst not providing further enlightenment on his artistic biography, do at least provide documentary proof of Caravaggio being in Rome no later than 1597 and paint a picture of this irascible, easily provoked sword and dagger carrying genius, who was living in a city where extreme violence and brutality were a daily occurrence.

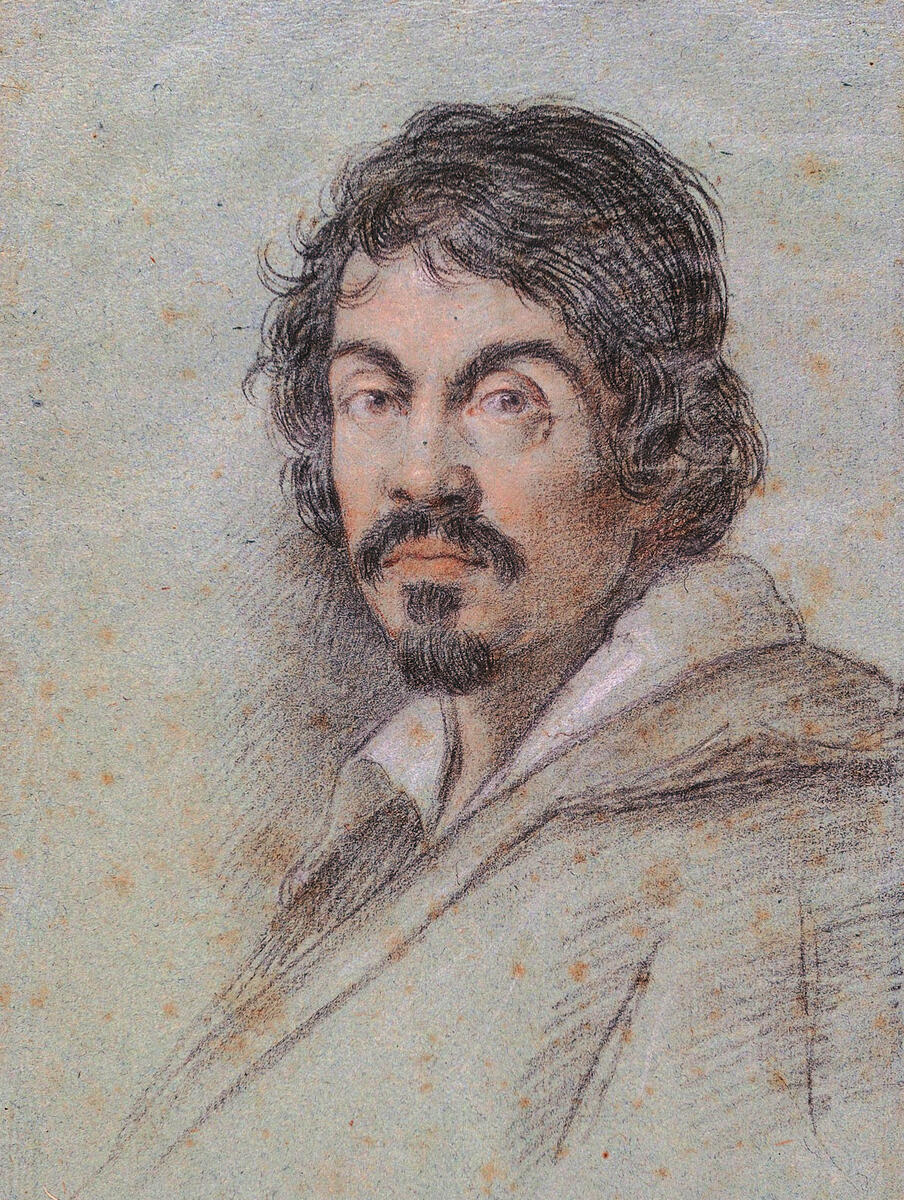

11 and 12 July 1597. Three men, one of whom was Caravaggio, were summoned to appear before the tribunal of the Governor of Rome and interrogated in connection with a case of assault, where a young barber’s assistant, Pietro Paolo Pellegrini, had been wounded. It is as a result of this police inquiry, that we have the best known description of Caravaggio’s appearance; the charges were mysteriously dropped, probably on the intervention of Cardinal del Monte.

4 May 1598. Arrested at 2am near the Piazza Navona for carrying a sword without a permit

19 Nov. 1600. Sued for beating a man with a stick and tearing his cape with a sword at 3am on the Via della Scrofa

2 October 1601. A young Tuscan art student, accused Caravaggio and friends of insulting and attacking him with a dagger outside the Spanish Embassy in the Piazza Campo Marzio. In what is thought to have been a premeditated attack, the young man had been stabbed in the back.

1602. Brought before the magistrates for assaulting a prostitute, who would not have sex with him; the slash on her face with a knife, an example of sfriegio, a mark of shame, doubly wounding for a prostitute, whose face was her fortune.

24 April 1604. A waiter serving artichokes was assaulted in an Inn on the Via Madalena.

28 May 1605. Arrested again on the Via del Corso for carrying a sword without a permit

29 July 1605. Vatican notary accuses Caravaggio of striking him from behind with a weapon

26 May 1606. – Kills Ranuccio Tommasoni in a pitched battle, much in the manner of contemporary warring drug gangs.

As already highlighted, the majority of paintings completed during the Renaissance period were based on Historical, Mythological and Biblical narratives, the models from which painters and sculptors worked were those of the Greco-Roman statues, which were being unearthed all through the Renaissance period and thereafter. In the late Renaissance and into the Baroque period, it was the sculptures of Michelangelo and the paintings of Raphael, which were regarded as the optimal examples of the divine in art, as painted by the likes of Annibale Carracci, Domenichino and Guido Reni.

Caravaggio was not the first painter to exploit the potential of lenses and mirrors to assist in the mimetic representation of the world around them. Most famously, there is evidence of such employment of optical devices in the paintings of Jan van Eyck (Adam and Eve in The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb), Robert Campin, (Portrait of a Man and a Woman) and Rogier van der Weyden in the early-mid 15th century and Hans Holbein in the early 16th century (The Ambassadors). However, Caravaggio, in David Hockney’s words, was to become the first Film Director, inventing Hollywood lighting, either by using a window high up in a room, or even making a hole in the roof of his studio to permit access of intense sunlight, painting the walls dark and in essence turning the room into a giant Camera Obscura, to project virtual images onto the canvas.

In fact, we have documentary proof that he used optical devices, as his first biographer, Giovanni Baglione stated, some small paintings portrayed in the mirror; Hockney claims that the mirror was in fact a concave mirror lens. With a mirror-lens projection, the usable image is never more than 30 cms, approximately a foot, irrespective of the size of the mirror. Outside this sweet-spot it is impossible to obtain a sharp image. Paintings made in this way are therefore restricted in size and can only be made bigger, by using a collage/montage method of building up a larger image from small images. Hockney and others such as Clovis Whitfield propose that he probably used the concave mirror for his early single heads, such as Boy Bitten by a Lizard, Boy with a Vase of Flowers and The Sick Bacchus, which are his first known works, painted between 1593-6 and group compositions such as the Fortune Teller and Cardsharps, the first works known to have been purchased by Cardinal del Monte.

Subsequently, when he entered the court of Cardinal del Monte in the Palazzo Madama around c1597, he would almost certainly have come into contact with Giambattista della Porta, scholar, polymath and playwright, with an interest in the occult, alchemy, astrology and credited with the perfection of the camera obscura and who was also referred to as the professor of secrets. With Galileo, both would have been regular guests, with whom Caravaggio would have been able to discuss his method of working and they might well have suggested the advantages of using a convex lens, rather than a concave mirror lens. The Sick Bacchus 26x21 inches, is a particularly apposite example, where Hockney in Secret Knowledge, persuasively suggests how the mirror-lens montage technique was achieved. If compared with The Lute Player, painted perhaps only a year later, versions of which were commissioned first by Cardinal del Monte and then by Vincenzo Giustiniani, there is an immediately obvious difference.

The paintings are now larger, 40x50 inches, much more of the figure is accommodated and appears to be situated in a more believable space and further back from the frontal picture-plane, which all points to a change of optical approach, namely the convex lens, which has the huge advantage of permitting a much larger field of view; although it does have the disadvantage of reversing the image; thus suddenly many more left-handed drinkers. With mirrors and lenses, one requires a strong light source to produce sharp bright images and as a direct result, one obtains correspondingly dark areas in shadow. Where the contrast between the light and dark is extreme, the term Tenebrism is used, whereas when the contrast is more nuanced, the term used is Chiaroscuro. Whilst Tenebrism provides the dramatic effect common to most of Caravaggio’s paintings, Chiaroscuro is a broader term, also covering the use of less extreme contrasts of light to enhance the illusion of three-dimensionality.

Roberta Lapucci, an Italian Conservation expert, in 2010, added a further dimension to the controversy, when she claimed that these virtual images may have been fixed on the primed canvas by the use of light-sensitive mercury salt, traces of which have been found on canvases. The image burned onto the canvas would last only 30 minutes and only be visible in the gloom; therefore, Caravaggio used a white lead paint to sketch, mixed with barium sulphate, which was luminous and of which traces have been found; in that way he could see what he was sketching.

From the middle of the 17th century for almost a hundred years, Caravaggio is all but forgotten, but then gradually like Vermeer, his reputation is reborn. First scant, but not entirely complimentary mentions are made by the renowned Classicist, Johann Joachim Winkelmann in 1750, but it is not until around 1890 that Wolfgang Kallab, whilst researching the catalogue of the Imperial Collections of Austria, detected a common style linking several early 17th century works of disputed authorship, putting forward the name of Caravaggio. At this time, not a single signed painting was known. This hypothesis was accepted by specialists such as Denis Mahon, Lionelli Venturi and finally in 1920 Roberto Longhi ‘nailed his colours to the mast’. Ever since, the name of Caravaggio has conjured up the public perception of the flawed genius, possibly the true originator of Modern Art.

Suggested Reading

Secret Knowledge: David Hockney, 2001. A revised addition now available

A History of Pictures: David Hockney and Martin Gayford, 2016: I found this a really fascinating read.

Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane. Andrew Graham Dixon: both this and that of Helen Langdon, tell a good story and are well researched, but the more recent paper by Clovis Whitfield illuminates the problem of Caravaggio’s early biography in Rome.

Caravaggio: Caravaggio: A Life. Helen Langdon

The Trouble with Caravaggio. A paper by Clovis Whitfield, 2014: very detailed, well researched and compellingly argued.

Suggested Internet sites

Factum Foundation: the making of the facsimile of the St Matthew Trilogy in the Contarelli Chapel, Chiesa San Luigi die Francesi: 2010

Art Optics: Caravaggio’s hand in the camera

Wikipedia: The Hockney-Falco Thesis, a good summary of the use of optics in painting, complete with the views of sceptical critics

Wikipedia: Biography of Giambattista della Porta

Wikipedia: Jupiter, Pluto and Neptune, Caravaggio

Wikipedia: The Lute Player, Caravaggio

Scipione Borghese – Puppetmaster of Caravaggio: 2013

Bacchus by Caravaggio as the visual diagnosis of alcohol use disorder: Frontiers in Psychiatry August 2013, Vol 4, Article 86