MV Railway History

Initial Schemes

There were several plans for railways in the Meon Valley in the 19th Century.

- 1851 – The Alton & Petersfield Railway proposed:

- Alton to Petersfield, with another line from Petersfield to Havant and a third from Petersfield to Fareham (via East Meon, West Meon, Droxford, Bishops Waltham, Hambledon, Wickham, Fareham)

- 1864 – London and South West Railway: From Ropley on the Mid-Hants Railway through West Meon and Warnford, before joining with the still-proposed Petersfield-Bishop's Waltham Line

- 1881 – By the Windsor, Aldershot & Portsmouth Railway: Farnham, Selbourne, West Meon, Hambledon, Cosham

- But would have needed 1 in 80 gradients and 3 or more long tunnels required.

- •1895 – A line connecting Basingstoke to Portsmouth, proposed by the Great Western Railway.

- But would have cost of £2,000,000!

The Meon Valley Line received Royal assent 1897. It was proposed by the London and South West Railway and built by the Contractor Relfe & Son of Plymouth.

Why the Meon Valley Railway over the Basingstoke to Portsmouth line, or at all? The land was mostly agricultural and thinly populated!

Apart from the high cost of the Basingstoke to Portsmouth line, there was an element of railway politics in the decision to build the MVR. Throughout the mid- and late- 19th century the LSWR's strongest rival was the Great Western Railway. The GWR had long sought to have its own line from the West Country to the booming ports of Southampton and Portsmouth. In 1895 the GWR had made a basic proposal for the Portsmouth, Basingstoke and Godalming Railway, from Reading, then south to Basingstoke, down the Meon Valley and then passing through Southwick and Bedhampton, where it would join the line into Portsmouth. The LSWR clearly believed that it should deny one of the last routes to the coast to its rivals! LSWR also felt that it would be advantageous to build a more direct line between London and the Portsmouth area (especially Gosport). Alton was becoming an important railway junction and a thriving market town, as was Fareham. A line between the two that ultimately connected London and Portsmouth was attractive.

Also a legend has it that Queen Victoria wanted a direct line to Osbourne House (via Gosport) rather than the very indirect train route she usually took!

At Warnford House, Colonel Woods grudgingly accepted that the Meon Valley line would be up and running and not the proposed Basingstoke to Portsmouth Railway which he, with others, had put up £500 each to promote, but which did not get past Parliament.

Planning

London and South West Railway proposed the MVR in 1897. Running for 22 ¼ miles (35.8 km) between Alton and Fareham. Building started in 1898.

The line opened in 1 June 1903 at a cost of £400,000. Thr West Meon viaduct alone cost £10,000!

It was built to Main Line Standards as an Express Route from London Waterloo to Gosport and a secondary route to Portsmouth. Single track, but it was built to accommodate a second track later.

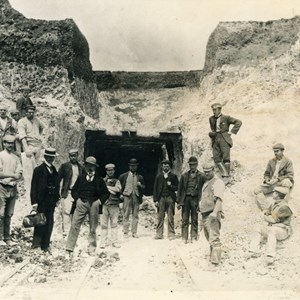

Construction

Construction started from the north end, Butts Junction and Farringdon working southward. Of course using Navvie power!!

It was only by the time West Meon was in sight that Steam Shovels were used to speed construction. From Droxford north it is Chalk, easy to dig but dry. South it is Reading Beds – Clay and Gravel and difficult to work and almost liquid when wet and like concrete in summer.

There were some benefits to the railway construction, all the local pubs experienced good business from the railway navvies, the White Horse in West Meon providing a tin hut in the garden for them to do their drinking.

Lynch House

As construction moved closer to West Meon, the house was used as a giant store to supply the needs of the navvies. Part of it was an eating place. A good dinner of meat, veg, and bread, cost six pence, and a pint of beer twopence.

The stables, now Lynch Hill Cottage, were converted into a bakehouse, capable of handling 3,000 20 lb loaves a day.

From the store stationery, clothing, groceries, even skipping ropes for the children, were available.

Opening Day

The opening day was Whit Monday, a bank holiday - Monday 1st June 1903.

There is, though no record of any formal celebrations or official opening ever taking place.

A private party was, though, held at Warnford House and Colonel Woods provided coaches and horses at Privett and Droxford to convey his guests back to Warnford where they were entertained at an all day party.

For the first day a free single ticket was offered to the next station, and from Wickham to Fareham cost 4 ½ d.

Warnford's nearest Station - West Meon

The platforms were almost 600 feet long, to accommodate the Waterloo-Gosport Express services.

The station building was identical to the others on the line, built of brick faced with Portland stone, all of a very high standard.

The Station Master’s house adjoined the offices which consisted of a booking hall, ticket office, station masters office, ladies' waiting room and a separate “Chinese Pagoda” outside toilet.

On the up platform was a lamp hut where the paraffin was stored for all the lights, including the signal lamps.

On the down platform was a waiting room having a black and red glazed tile floor.

On each of the platforms stood a water column to supply the locomotives with water, West Meon being the half way point between Alton and Fareham.

There was a wooden footbridge to allow passengers to cross between platforms.

The goods yard was quite spacious with two sidings for goods traffic, a Goods shed, a five ton crane (hand wound) and a short dock for the loading and unloading of cattle. A long siding ran for 349 yards southwards beside the running line, so that a goods train could be shunted out of the way to allow the passage of the Gosport to Waterloo service. Each station had at least one coal merchant and West Meon had no less than three on starting.

Each station on the line had four sidings, or “roads” as they were called. The back road was always the “coal road”, and was used exclusively by William Stone from 1916, until closure in 1955.

Westbury House provided a considerable amount of traffic, with whole wagonloads of coke for their central heating boiler, all of which came from Hilsea Gasworks near Portsmouth.

The middle road freight varied between artificial fertilizer, seed potatoes, heavy farm machinery -that was unloaded using the 5 Ton hand wound crane - and eventually when the sugar had been extracted, the sugar beet pulp came back to West Meon to be used as cattle feed.

The short siding allowed UP trains to reverse and pick up a horse box, whilst the cattle dock could be used for sending and receiving farm animals and, also at times, those potatoes that were deemed to be too small for human consumption, were loaded into wagons before being sprayed with a purple dye and sent away to be used as cattle feed.

Early History

Initially, there were between 8 and 11 services a day (4 and 6 coach). Twice a day the line was used by a London–Gosport fast express service.

As was expected, the bulk of traffic came from shipping agricultural produce. On the MVR this included watercress, wheat, fruit (especially strawberries and apples), milk and cattle.

- There were local 'pick-up/set-down' goods services, calling at every station.

The LSWR put on special market-day trains, with both passenger carriages and livestock cars, allowing farmers to accompany their livestock.

The expected London through-traffic never materialised, and after only a few years the London to Gosport services were cut back. In 1915 the regular London traffic was suspended totally, and the services were never reinstated. From then on the MVR only handled regular traffic between Fareham and Alton.

The line then attained the status of a rural branch line.

After WW1

After WW1, with the expected traffic not materialised, economies were made;

- Privett signal box was closed and all trains now used the down line.

- Staff numbers were reduced.

- Only West Meon retained a Stationmaster post – at other stations there was a Porter-in-charge.

- The wooden footbridges were all dismantled by the mid 1930s.

- Goods sheds (except Farringdon and Wickham) were dismantled.

By 1923, LSWR was merged into the Southern Railway. There were now only six or eight services a day, mainly formed of two- or three-coach trains.

Goods services remained vital to the line, with a twice-daily service – one trip south-bound and one north-bound.

The 1930's

In 1931 a further down-grading of the MVR took place when the track at Butts Junction was relaid. The signal box was removed and the MVR's direct connection with the Alton Line to London was removed. MVR trains now ran direct to a bay platform at Alton station. Trains could not run direct from the Alton Line to the Meon Valley as they had been able to – if this was required trains had to shunt from one line to the other.

This change spelt the end of the MVR as an integrated part of the railway network – it was now simply handling stopping local traffic with none of the fast inter-city express traffic that the line was built to handle and that used the line in its early days.

Wartime Meon Valley Railway

The line was yet again used lightly compared to other railways in the region. There was, though, an increase in goods traffic supplying the naval dockyard at Portsmouth. Passenger services had a box van added to cope with the near-constant stream of parcels and luggage to and from Portsmouth. A few troop trains used the line late at night.

There was a brief spell of intensive use during the build-up to D-Day when huge numbers of men and equipment had to be moved to the south of England, kept in readiness and finally transported to ports. Large numbers of Tanks were moved by rail to Mislingford goods yard where they were dispersed.

The tunnel at West Meon and the viaduct were two of the most important places on the whole line. Throughout the course of the war they were guarded by members of the Home Guard every night (West Meon, Warnford and Woodlands Home Guard, officially known as "D" Company, 15th Hampshire Regiment). This was against the threat of paratroopers and guards were placed at either end of the tunnel and viaduct. Both places had to be walked the full length at least once every night. To walk the length of the tunnel meant a journey of almost a quarter of a mile. Some members of the Home Guard would take a very unofficial trip to the New Inn or the Red Lion for a very unofficial pint or two. Upon their return they would be challenged with, “Halt. Who goes there?” The reply inevitably was, “Who the .... hell do you think it is?”

The Special Train

Friday, 2nd June 1944, a “special train” travelled down the Meon Valley Line from Alton and stayed in the siding at Droxford for most of the weekend.

The “special train” was to stay in the siding at Droxford until the evening of 5th June. During that time, most of the people on that train, including their secretaries, travelled down to Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force at Southwick House to oversee the final plans for D Day. The train passengers included;

- Mackenzie King (Canada), Winston Churchill, Peter Fraser (New Zealand), General Eisenhower, Sir Godfrey Huggins (Australia), General Smuts (South Africa).

Wartime Damage

In 1941 the Luftwaffe chose to pay us a visit. A formation of Junkers 88 bombers over Bishops Waltham were attacked by Spitfires and made to disperse.

A lone bomber flew east and dropped bombs at Droxford Station and machine-gunned the buildings before flying on up the line At West Meon the bomber spotted the tunnel and bombed the tunnel mouth. Fortunately for everyone the bomb aimer was a rotten shot. He missed the tunnel mouth by some distance but struck the top of the cutting near Vinnells Lane bridge. The bomb slithered down the slope before hitting the track and blowing up several yards of rail and sleepers.

After the War

The Southern Railway was nationalised into British Railways in 1948. No immediate changes were made, with the standard 2-car services running around five services a day. Problems were coming, as the rise of private car ownership and a major shift of local goods traffic from rail to road saw the MVR become increasingly uneconomical to run. Services were gradually run down. 1951 saw the end of Sunday services. Shortly after, it went down to 4 services per day.

During the early 1950s, British Railways drew up its “Modernisation Plan”. This included the;

- Withdrawal of steam locomotives.

- Electrification of its main trunk routes.

However, the plan also listed several lines that could be closed either because they were redundant in a nationalised, competition-free network or because they were unsustainable to operate.

To save ~£30k per year, the MVR was thus marked for closure to Passenger Services from 5 February 1955.

The Closure

On 5 February 1955, the MVR closed to passenger services and totally closed from Droxford to Farringdon. It was still open on its extremities for goods.

The Last Train left Alton at 4.30 pm “down” and Fareham “up” at 6.48 pm.

This wasn’t the last train, though. On the 6th, “The Hampshireman” left Waterloo on a circular route. This was a special train organised for Railway Enthusiasts;

- Woking to Petersfield, Fareham then north through the MVR.

The track from Droxford to Farringdon and the Viaduct were dismantled over the next 2 years.

Until 1962, goods ran to Droxford, and until 1968 to Farringdon.

The Farringdon to Butts junction track was lifted from 1969-70.

Knowle Junction closed in 1970 and the track taken up to Bridge 12 north of Wickham.

The last remaining section between Mislingford and Droxford was lifted in 1975.

Not Quite the End!

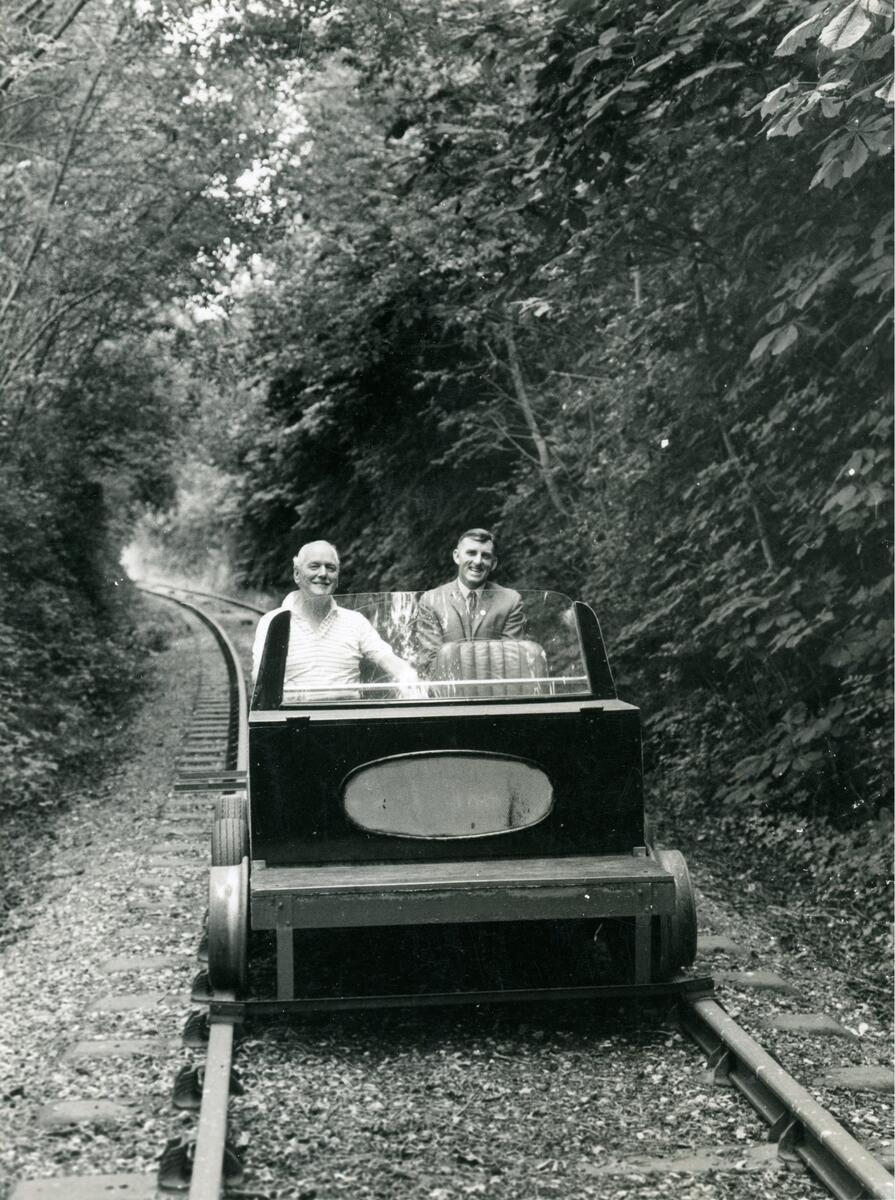

Charles Ashby purchased Droxford station and the right to run trains over the railway to just north of Wickham (Bridge 12) – 4.5 miles. He used it for testing a design of railbus that he had developed called the Sadler Rail Coach or 'Pacerailer’. This was essentially a bus-style vehicle.

This dream ended in May 1970 when it was severely damaged in a fire. After that Charles Ashby used two small Ruston-Hornsby diesel shunters and two ex-BR carriages to operate private-charter trains for a short time.

The last standard gauge vehicle to run on any part the Meon Valley Railway was an Austin Mini-based railcar owned by Charles Ashby.